Note: This 2011 report was researched and written by the Colorado Futures Center at CSU team when previously attached to the Colorado Economic Futures Center at the University of Denver.

- Download this report: General Fund Revenues and Expenditures: A Structural Imbalance

- The 2013 study is available here: The Colorado Sustainability Study

Economists talk in terms of whether a phenomenon is cyclical or structural. High unemployment, for example, can be a cyclical problem when fluctuations in economic activity trend downward – many laid-off workers will be rehired when the cycle resumes an upswing. Structural unemployment, on the other hand, happens when underlying conditions change fundamentally, resulting in a mismatch between the demands of the labor market and how the labor force has been trained. This can lead to a prolonged period of high unemployment.

Colorado’s budgetary woes are both cyclical and structural. The extraordinary revenue shortfalls that have plagued state government for much of the last decade were caused, in large part, by two extreme economic downturns, the latter of which was by many measures the worst since the Great Depression. When the economy improves, tax collections will pick up. But absent major changes in policy, a structural imbalance underlying the fiscal workings of state government will ensure that Colorado’s budget problems persist for many years to come.

The bottom line is this: Even a strong recovery and sustained job growth over the next decade and a half will not produce enough income and sales tax revenue to afford Colorado’s share of Medicaid funding and the state’s payment for public schools under current constitutional and statutory provisions. Together with the rising (although more stable than in the past) cost of the state’s prison system, the two biggest programs in the state General Fund will continue to crowd out higher education and other programs competing for the same tax dollars.

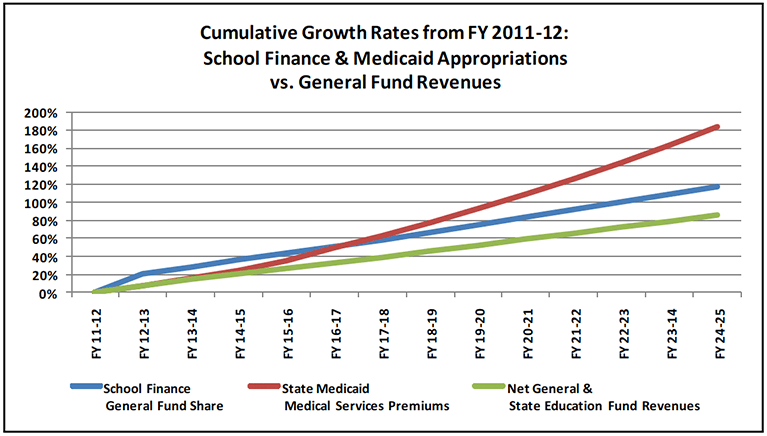

The Center for Colorado’s Economic Future created models that projected General Fund revenues and costs for the three largest General Fund program areas – K-12 education, Medicaid and corrections – from FY 2011-12 to FY 2024-25. Our forecasts show that the state’s annual expenditures for Medicaid medical services premiums will nearly triple during that period (184 percent). What the state pays every year to help fund public schools will more than double (118 percent). General Fund tax collections, however, will grow only 86 percent.

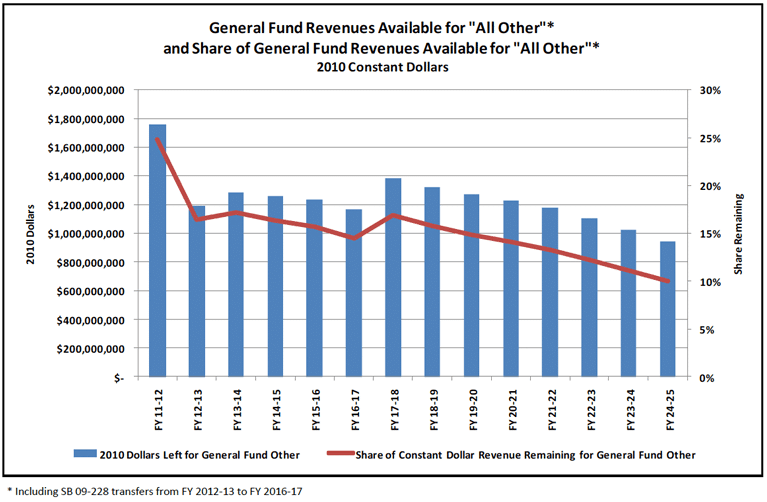

After increases for schools, Medicaid and corrections are funded, the share of the General Fund left over for other programs will be cut by 60 percent over our forecast period. Not only will the nominal amount of dollars remaining for higher education, human services, the court system and other programs drop, but the purchasing power of those dollars will fall by about 46 percent due to inflation. Meanwhile, Colorado’s population is expected to rise about 26 percent, to more than 6.7 million people. That will mean more college students, more court filings, higher caseloads in the Department of Human Services, and so on. Some of these programs will grow at rates greater than inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index.

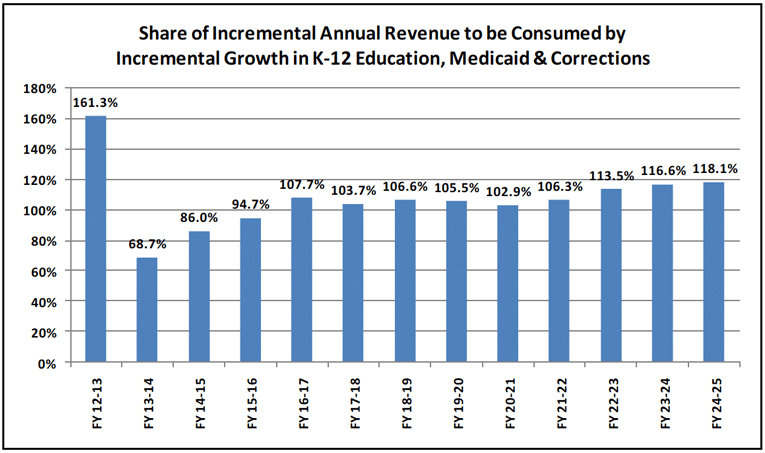

We project that General Fund diversions for transportation, capital construction and reserve increases will be triggered in FY 2012-13, as required by SB 09-228, due to a rise of more than 5 percent in state personal income. The diversions will continue for five years, expiring after FY 2016-17, leaving no continuing General Fund support for these purposes. Money available for programs other than education, Medicaid and corrections will be even less if state legislators and the governor continue the General Fund diversions. Our forecasts show that all “new money” – the amount of growth in revenue each year over the prior year’s revenue – will be consumed by schools, Medicaid and corrections for nine years beginning in FY 2016-17.

Colorado cannot expect to grow its way out of its budget problems. The Center’s state economic model, which is largely based on national economic indicators forecast by Moody’s Economy.com, shows a healthy recovery from the current economic downturn with rates of job growth commensurate with the recoveries of the late 1980s and mid 2000s and sustained job growth through 2025. However, that level of economic activity will fail to generate revenues sufficient to keep pace with the major programs driving General Fund expenditures. From FY 2011-12 to FY 2024-25, our projections show state K-12 education costs growing at a compound annual rate of about 6 percent and Medicaid expenditures growing more than 8 percent annually. But General Fund revenues will grow at a compound annual rate of only 5 percent over that period. From this we conclude that the state budget faces a persistent structural imbalance.

The Center’s revenue model was generated econometrically by separately forecasting each major tax revenue stream and combining them into a General Fund total. The tax revenue streams were forecast using parameters estimated from a series of structural relationships between the historical performance of each tax and major macroeconomic indicators. On the expenditure side, the K-12 model projected the state share of education costs using a simulation that incorporated the mill levy freeze enacted in 2007, the expected performance of local property taxes and funding requirements resulting from school enrollment growth and inflation. Medicaid was forecast by first separately projecting caseload growth by recipient categories based on State Demography Office population projections. The Congressional Budget Office’s national cost growth projections for Medicaid were then applied to these caseloads to forecast the total growth of medical services expenditures. Corrections expenditures are based on a prison population forecast that takes into account recent changes in sentencing laws and grows with the population of males ages 18 to 30, as projected by the state demographer.

Among our study’s other findings:

- Colorado’s revenue system is more volatile than the revenue systems of the 50 states combined. This volatility stems from the General Fund’s reliance on individual income taxes, which has increased markedly over the last 30 years and subjects state revenue collections to the ups and downs of capital gains realizations. Volatility, which works in state government’s favor during boom times but can be devastating for the General Fund budget during economic downturns, makes it much more difficult for state economists to forecast tax revenues.

- The state portion of total school funding, which has risen to 63 percent from 55 percent in FY 1993-94, will grow to 70 percent by FY 2024-25. The local share, which is supported by local school property taxes, will continue to decline. This trend will persist despite a recent attempt to stabilize the property tax share through legislation that froze school district mill levies. Schools, excluding K-12 categorical programs, will consume 53 percent of General Fund revenues in FY 2024-25 compared with 45 percent in FY 2011-12.

- Medicaid expenditures will grow strongly due to costs associated with the high rate of health care inflation and a burgeoning number of older enrollees – a trend driven by the aging of the baby boom generation who make up the most expensive part of the caseload. Many of these older enrollees will require long-term care at home or in skilled-nursing facilities. Medicaid medical services premiums will account for 27 percent of General Fund revenues in FY 2024-25 compared with 18 percent in FY 2011-12.

- While expenditures for the state’s prison system will continue to grow, the share of General Fund revenues consumed by corrections will drop from about 9 percent in FY 2011-12 to about 7 percent in FY 2024-25. The department of corrections was one of the fastest-growing portions of the General Fund budget as the prison population grew rapidly in the 1990s and 2000s. But this growth has leveled off and even declined recently because of changes in sentencing laws, a downward trend in felony court filings and slower growth in the 18- to 30-year-old demographic cohort most likely to be incarcerated. Our projections show the prison population rising less than 7 percent to about 24,110 in FY 2024-25 from the current population of 22,600.

The long-term, persistent structural imbalance between General Fund revenues and expenditures will not be corrected without structural solutions. Below are the policy directions we have identified and will pursue further in the next phase of the project:

- A long-term planning approach to complement the annual budget process. Structural problems take years to develop; they will not be resolved overnight or during a single budget process. A long-term plan should address the persistent fiscal imbalance. It would be adjusted as necessary when economic circumstances and policy decisions exert different pressures on revenue and expenditure trends.

- Budget rules that address the volatility of revenue streams. Given Colorado’s volatile tax structure, the management of state finances requires an explicit recognition of that volatility and rules for managing it. A budget stabilization fund would capture revenues generated during unusually large upswings and save it to cover shortfalls that result from large negative swings.

- A redefinition of the state-local partnership for funding schools or a new way to fund schools. Tax-base erosion under the Gallagher Amendment, property tax limits imposed by the school finance act and TABOR, and the mandated cost increases of Amendment 23 have shifted the burden of funding K-12 education substantially to state resources. The partnership between state and local revenues should be rebalanced or Colorado should consider a new way to pay for public schools.

- Strategies to address programs, particularly Medicaid, which grow faster than revenues. As Colorado’s large baby boom cohort ages, the state will experience slower per-household revenue growth coupled with greater Medicaid expenses. Strategies include planning for cost increases, more cost-effective ways to deliver Medicaid services and ways to improve the productivity of current revenues.

- Stable and permanent funding sources for transportation, capital needs and controlled maintenance. In the long term, the General Fund cannot provide surplus funding for transportation, capital needs and controlled maintenance. Other financing mechanisms will need to be identified.

- Reforms of the revenue system. Colorado’s current revenue system could be made more productive and flexible with measures that broaden revenue bases to capture a larger share of economic activity. This may be accompanied by lower rates and still result in a more productive and equitable revenue system. In addition, reconsidering the earmarking of certain revenues for specific purposes could increase elected officials’ flexibility to deal with changing circumstances in a timely manner.